1-2~5 Geology of Kushiro

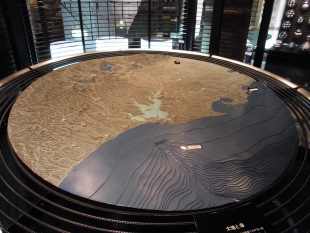

1-2 Geology of Kushiro

The geology of Kushiro has been influenced by glaciation, changing sea levels, and volcanic activity. Over time, distinctive landscapes developed, including wetlands and a variety of different marine environments.

Kushiro Wetlands

The Kushiro Wetlands began forming some 6,000 years ago when a period of sustained global cooling caused sea levels to fall, exposing previously submerged coastal plains. The wetlands support thousands of species of plants and animals, including the Japanese crane (Grus japonensis, called tancho in Japanese). The Kushiro Wetlands are the largest in Japan, covering 28,788 hectares.

Volcanic lakes

During the last ice age, several calderas formed to the north of the Kushiro Wetlands. Calderas are craters that take shape when the central part of a volcano collapses in on itself. The craters that formed here filled with water to become Lake Akan, Lake Mashu, and Lake Kussharo, the latter of which is the largest caldera lake in Japan. Lake Kussharo feeds the Kushiro River, which traverses the wetlands and empties into Kushiro Bay.

Kushiro Bay

Kushiro Bay is a geologically diverse environment that supports a wealth of marine life. The bay is divided into two sides by an underwater canyon. The west side has a gentle, sandy shoreline, and the east side has steep, rocky cliffs. The marine life of the Kushiro Submarine Canyon and the shoreline environment is distinct: Flatfish flourish in the sandy shoreline area and deep-sea shrimp and crabs populate the slopes of the marine canyon.

1-3 Kushiro tapir

The tapir is a large, herbivorous mammal resembling a pig, but with an elongated, prehensile snout. The four known extant species of tapir, all endangered, are found in South America, Central America, and Southeast Asia. Millions of years ago, several now-extinct species of tapir roamed North America and Eurasia.

This fossil is the upper jaw of a newly discovered species, the Kushiro tapir (Colodon kushiroensis). Paleontologists believe the Kushiro tapir lived around 38 million years ago, based on the geological strata in which the fossil was found.

Ice age migration

The fossilized molar teeth of the Kushiro tapir are similar to those found in tapir fossils from North America, leading paleontologists to conclude that the Kushiro tapir likely came to Hokkaido from North America via the Eurasian continent. During the last ice age, when sea levels were much lower, Hokkaido was connected by land to Eurasia via the island of Sakhalin.

A rare discovery

This fossil is unusual both because it is the only known remnant of a Kushiro tapir and because fossils of this size are rarely found intact. The specimen is 10 centimeters long and 9 centimeters wide, with nine teeth, including the premolar and molar teeth. It was discovered by junior high school students in 1968 near a cliff in Tomachise, to the east of Kushiro.

1-4 Coal: Natural Fuel from the Wetlands

The Kushiro Coalfield formed about 38 million years ago from the rich peatlands around Kushiro. Peat is created in wetlands and bogs when wet conditions and cold temperatures prevent dead plant matter from decomposing fully. These layers of partially decayed vegetation slowly accumulate as peat, and then gradually fossilize into coal as they are compressed under the weight of additional layers over the course of millennia. The Kushiro Wetlands contain Japan’s largest peatland, and the peat found there may one day form into coal.

The Kushiro Coalfield has more than 10 coal seams (layers of coal that are thick enough to be mined), each up to 5 meters thick. These seams, located east of the city of Kushiro, spread out under the seabed. Coal has been a major source of income and employment in Kushiro, contributing to the region’s development, since large-scale mining started here in 1920. At one time, the Pacific Coal Mine in Kushiro was one of the largest in Japan. Today, the Kushiro Coal Mine is the only underground mine still operating in Japan. It produces around 300,000 tons of coal a year.

1-5 Kushiro Wetlands

Many rare and native species of plants and animals inhabit the Kushiro Wetlands, including Japan’s only known population of the endangered Japanese crane (Jp. tancho; Grus japonensis), as well as species that have been in the area since the last ice age. The primitive lowland environment, forming the largest wetland area in Japan, has changed little since sea levels fell around 6,000 years ago. The Kushiro Wetlands are protected under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty for the conservation of wetland areas.

Around 30,000 years ago, during the coldest part of the last ice age known as the Wisconsin glaciation, sea levels were 100 meters lower than they are now. At that time, a land bridge connected Hokkaido to the Eurasian continent through the island of Sakhalin, allowing animals to migrate from the continent to Hokkaido. Over several millennia, temperatures rose, causing glaciers to melt and sea levels to rise, and the area that is now the Kushiro Wetlands became a bay.

Changing seas

Some 6,000 years ago, temperatures and sea levels dropped again, and this low-lying area became landlocked. Prehistoric societies left mounds of discarded shells along a plateau bordering the wetlands. These shell mounds show how sea levels have changed over time, indicating that the coastline was once further inland. Several lakes and water reservoirs remained after the sea retreated.

This English-language text was created by the Japan Tourism Agency.

このページに関するお問い合わせ

生涯学習部 博物館 博物館担当

〒085-0822 北海道釧路市春湖台1番7号 博物館

電話:0154-41-5809 ファクス:0154-42-6000

お問い合わせは専用フォームをご利用ください。