2-11~15 Early modern and Modern era of Kushiro 2

2-11 Traditional Workwear for Fishing

Fishing in Kushiro was tough work, particularly during the harsh winter months. Before modern thermal fabrics, fishermen kept warm by wearing short outer coats called sashiko (also known locally as donza). The coats were named for sashiko, or “little stabs,” a type of running stitch used to quilt together layers of indigo cotton or hemp. Featuring stitchwork patterns, these coats were practical but also decorative. Each coat was passed down through successive generations of a family.

Sashiko coats were shaped like a kimono, but with narrow cuffs and multiple layers to keep in body heat. It was usually the job of the fisherman’s wife to make and repair the coats during the winter, in preparation for the following year’s fishing season. Sashiko coats were common in Hokkaido from the Edo period (1603–1867) until imported woolen fabrics and cotton flannels became widespread in the Meiji and Taisho eras (1868–1926).

2-12 A Thriving Town

Kushiro was a center of fishing, timber, coal, and shipping from the late Meiji era (1868–1912) on. As the economy boomed, the population grew, and Kushiro was designated a city in 1922. A newspaper was established, and more stores opened to cater to the influx of settlers.

Winter temperatures in Kushiro often stay below freezing. In the Meiji era, large woolen shawls called kakumaki, worn over a kimono, became popular for women. Men wore the niju-mawashi, a sleeveless woolen coat with a cape and fur collar. This was based on the Inverness coat from Scotland, and could easily be worn over both Japanese- and Western-style clothes.

Kushiro attracted enterprising individuals like Sasaki Yonetaro (1868–1951), who moved from a small town north of the city to open a store selling rice and other daily necessities in 1901. He became an influential figure in Kushiro, rising to president of the city council and writing the first history of the Kushiro area. His store’s signboard, with the name of the shop in gold leaf, is on display at the museum.

2-13 Kushiro During World War II

Cities all over Japan came under attack from the allied forces during World War II. Women and children wore padded fabric air-raid hoods to protect them from falling debris and fire. One month before the end of the war, Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters flying from aircraft carriers of the United States Third Fleet launched air raids across Hokkaido. On July 14 and 15, 1945, the air raids targeted Kushiro among other cities in Hokkaido and northern Honshu.

During those two days Kushiro was attacked eight times. The main targets were factories, railroads, fishing boats, and schools. The heavy attack on the downtown area is believed to have been aimed at demoralizing the population. The Nusamai Bridge in downtown Kushiro was damaged but not destroyed. One of its Art Deco stone obelisks fell into the river (the top of the pillar is on display at the museum entrance), and its steel sides were strafed by machine-gun fire. A piece of steel plate from the bridge, over 10 millimeters thick and pierced with bullet holes, is on display at the museum. Over those two days, 193 people died and more than 500 were injured. Around 60 percent of the deaths were caused by fires resulting from the air raids.

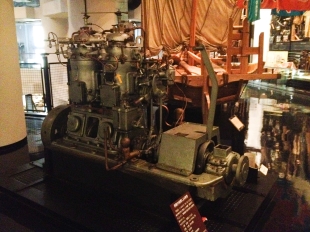

2-14 Hot-bulb Engine

The hot-bulb engine (yakidama) was a simple internal combustion engine first developed in the United Kingdom in 1886. An early version, the Hornsby-Akroyd oil engine, was brought to Japan a few years later and adapted by domestic manufacturers. The hot-bulb engine was simple to use, easy to manufacture, and ran on cheap fuel. The engine was adopted in earnest by fishermen in Kushiro after a fatal offshore accident in 1913, when some tuna boats were caught in a heavy storm offshore. They could not get back to the port in time and 63 fishermen died. The hot-bulb engine cut down the round-trip time to the fishing grounds and opened up a wider fishing area.

Boats with a hot-bulb engine were called ponpon boats for the rhythmical sound of the engine. Hot-bulb engines were gradually replaced by more powerful diesel engines in the 1950s. The hot-bulb engine on display in the museum was made in 1952.

2-15 The Agricultural Light Railway: A Community Lifeline

The Japanese government promoted migration from other parts of the country to Hokkaido beginning in the 1860s, but the lack of infrastructure made it difficult for people to inhabit inland areas of the island. Even in the 1920s, the National Railway from Sapporo only serviced eastern Hokkaido’s coastal towns, and the inland roads were often dirt tracks, impassable in adverse weather conditions.

To open the inland areas of eastern Hokkaido, the government built the Agricultural Light Railway, with narrow gauge tracks to reduce costs. The first of these rail lines opened in 1924 from Attoko Station, east of Kushiro, to Nakashibetsu farther inland. Horse-drawn vehicles ran on the tracks, but as the volume of traffic increased, they were replaced with gasoline-powered locomotives.

These trains were lifelines for frontier settlements, transporting people to Kushiro and crops and dairy products to market—even serving as an ambulance when needed. At a time when many households in the area had no electricity and no telephone, people went to the nearest railway office to make phone calls. Because of the narrow gauge of the rails, the train sometimes tipped over in snowy conditions, and community members would band together to pull it upright again.

Diesel engines were introduced after World War II, but the trains were still single cars, much like trams. In the 1960s many of the small rail lines had been converted to roads. By 1972 only a few railway routes remained open in eastern and northern Hokkaido, as the lines that had played such an important part in the development of the region were successively removed or abandoned. Remnants of these lines can still be found in the area’s fields and forests, and some of the old railway cars have been preserved in Tsurui Village north of Kushiro and at Okuyukiusu Station, a former station in the town of Betsukai east of Kushiro.

このページに関するお問い合わせ

生涯学習部 博物館 博物館担当

〒085-0822 北海道釧路市春湖台1番7号 博物館

電話:0154-41-5809 ファクス:0154-42-6000

お問い合わせは専用フォームをご利用ください。